World-class Cities vs. Socially Just Cities

MSc. Urban Development/International Planning Dissertation

Development Planning Unit (DPU), University College London (UCL), London, U.K.

JNNURM, India: An Urban Development Policy for ‘World-Class Cities’ or ‘Socially Just Cities’?

A Conflicting Paradigm

– Neha Soni

Abstract

The dissertation explores ‘strategic indicators’ to measure social justice in urban policy and planning. It does so in the context of defining social justice in urban development, broadly categorized into distributional and institutional contexts. These performance measures are explored for the strategic interventions that could possibly be made to guide the development in the pursuit of social justice in today’s global cities.

It discusses the conflicts and tensions that cities face due to the global challenges and local demands. It further argues that as cities are increasingly visioning themselves to be world-class in the run to be globally competitive, the vision is becoming exclusionary, selecting the rich and neglecting the poor, creating the unequal world. To address this social injustice and create inclusiveness, there is an immediate need for careful planning and policies in context to the performance measures explored here to re-frame the vision for cities to create ‘socially just cities’ rather than ‘world-class cities’.

Executive Summary

This dissertation study aims at understanding the conflicting paradigm that cities are facing today, especially in developing countries like India. The last decade of the 20th century marks opening of the world economies to the benefits of trade, deregulated capital, and neo-liberal policies – the major facets of globalization The challenges of globalization are finding their expressions in the cities and in its urban policies and programs. These global competitions are scripting ‘world-class visions’ for cities. But these visions are increasingly becoming exclusionary, selecting some and neglecting some, creating the unequal world. There appeared increased poverty and slum formation, while social justice and quality of life diminished. The cities are pressurized between global-local forces competing internationally and at the same time serving the increasing urban population. In developing countries, infrastructure development and service delivery became two major tasks for these world-cities. This conflicting paradigm and tension that is being experienced by the cities are critical to understand and examine for making our cities ‘socially just’.

In light of this discussion, the case of Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) has been analyzed. This policy is no different than any urban policy being influenced by the global and local processes for creating world-class cities. The economic development with soaring growth rates, expanding trade and markets, industrial development, and high foreign investment have also led to rapid urbanization in a short period. There are now serious deficiencies in urban infrastructure and services like housing, transport, water supply, sanitation, and social infrastructure. Recognizing these challenges of acute urban crisis, JNNURM was launched for the planned development of cities with world-class vision. This being the biggest national level initiatory urban policy, there is a need to understand how it is shaping the development of cities in India which is vital to creating ‘social justice’ within urban development.

Overall, the dissertation first discusses the conflicting paradigm between creating cities with world-class vision and the lack of social justice dimension within this vision. The concept of social justice is then established to define what exactly social justice could mean in today’s urban situation. This has been analyzed in two contexts; distributional and institutional. The criteria and indicators of social justice in terms of the distribution of material goods and the institutional process in which the distribution takes place are discussed. These performance criteria are then analyzed in-depth within the NURM policy. Finally, the findings derived through this analysis have been concluded, which may be useful for making urban policies and programs more socially just.

The research methodology included identification of the topic, literature review, and data collection. The selection of the subject was timely when the policy just started to be in effect. The literature review included theories on the subject of social justice. Different viewpoints were bridged to make a personal position on the topic for analysis. A theoretical framework with a set of criteria and indicators was developed to measure the concept in the policy. Both qualitative and quantitative data have been obtained through a literature review as well as semi-structured interviews. Mostly, secondary data has been referred to through the writings of experts on the case. The main limitation has been the lack of accessibility to much primary information and no field visit for first-hand experience of the issues.

Compressed Version

Introduction

The world economy has shaped the life of cities for centuries. The global vision provides opportunities for a new visibility and articulation of localities, giving new instruments to reshape themselves. The role of world cities is constantly changing in relation to the evolving world systems. At a global level, the increasing role of trans-national corporations in developed as well as developing nations, formation of new integrated trading blocs, financial as well as socio-cultural flows, persistence of international debt and the attendant austerity measures are all finding their expressions in today’s cities. This results in producing new modern office towers, commercial free trade zones and enterprise development areas in cities. In order to attract and retain these global corporate, increased pressures is placed on local governments to provide a high standard of services which will improve the efficiency and quality of life in the cities.

At local level, the governments are faced with increased competition for provision of basic services to the needs of the general population and urban poor, versus investing in the specialized services which are for more sophisticated international business interests. These are raising serious questions of adequate service delivery. Thus, there is interaction of two processes; globalization of economic activities at large and complex scale on one hand, and growing service intensity in the organisation of all industries on the other. In this context, globalization has become a question of scale and added complexity.

The increase in inequality can be traced almost directly to liberalization which is also a proximate cause of globalization The increase of informal sector due to collapse of formal urban employment in the developing world is seen as a direct function of ‘ liberalization’. Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) were widespread in the developing world by this time; these austerity programs involved substantial budget cuts and price rises, which impacted particularly strongly on the urban poor.’ Globalization was viewed as offering opportunities for cities, as a progressive force for creating prosperity in a global market civilization where inequalities would gradually overcome. The governments have adopted more market friendly policies to attract much needed foreign capital in this border less global economy. The analysis points to the diffusion of wealth and affluence in the world economy – ‘the trickle-down effect’. But, this ‘Trickle-down effect’ occurred to a relatively small part of society.

The contradictory roles demanded of city governments in the wake of global competitiveness and local needs, there seems to be struggle between creating world-class cities and socially just cities. There seem to be inter-connectedness between globalization and social exclusion, where world-class vision is the ‘vision of few’. The social justice perspective provides a way of understanding the relational and institutional dynamics which include some and exclude others in the connected yet polarized global cities. As the economies are being more integrated globally, the cities struggle to be inclusive to integrate social goals with local economic development. The challenge remains at the policy and planning of cities where the pattern of urban development is being shaped by the global forces.

Defining Social Justice in Urban Development

Urban theorists debate the social justice discourses on many varied concepts and approaches. One of the widely referred concepts has been Young’s approach based on not just distributional context, but also institutional. Further to Harvey’s approach of ‘Just distribution justly arrived at’, Young criticizes the definition of social justice predominantly focusing on distributive paradigm i.e. distribution of wealth, income and positions, which ignores the institutional context within which those distribution takes place. Young emphasis the ‘Institutional context’ in a broader sense than mode of production and this includes any structures or practices, the rules and norms that guide them, the language and symbols that mediate social interactions within them in the institutions of state, family and civil society. Hence, she defines social justice as the ability of people to participate in the decision-making process to determine their actions and to further their ability to develop and exercise their capacities. Further, Fainstein refers to ‘social justice as Realizing the Just City’. He claims that the just city is the appropriate object of planning, the just city consist of a set of values; democracy, equality, diversity, growth and sustainability. It is ‘Just access to and control of resources and decision-making power’.

Considering the different positions on concepts of social justice, the definition of social justice can be based on guiding principles broadly categorized under ‘distributional and institutional context’. These guiding principles and the criteria should be observed from goals, through the process/implementation till the outcome/impacts of any planning & policy practice to attain socially just cities. Under this framework of social justice, any urban policy can be analysed. For the case of NURM, the definition of ‘Socially Just Cities’ can be articulated as, ‘Cities creating development through urban policies & planning which are established by inclusive visions, leading to Distributional & Institutional equity’. With reference to this definition, the performance criteria provides framework to understand how far NURM promotes socially just cities through its ‘means’ and ‘ends’.

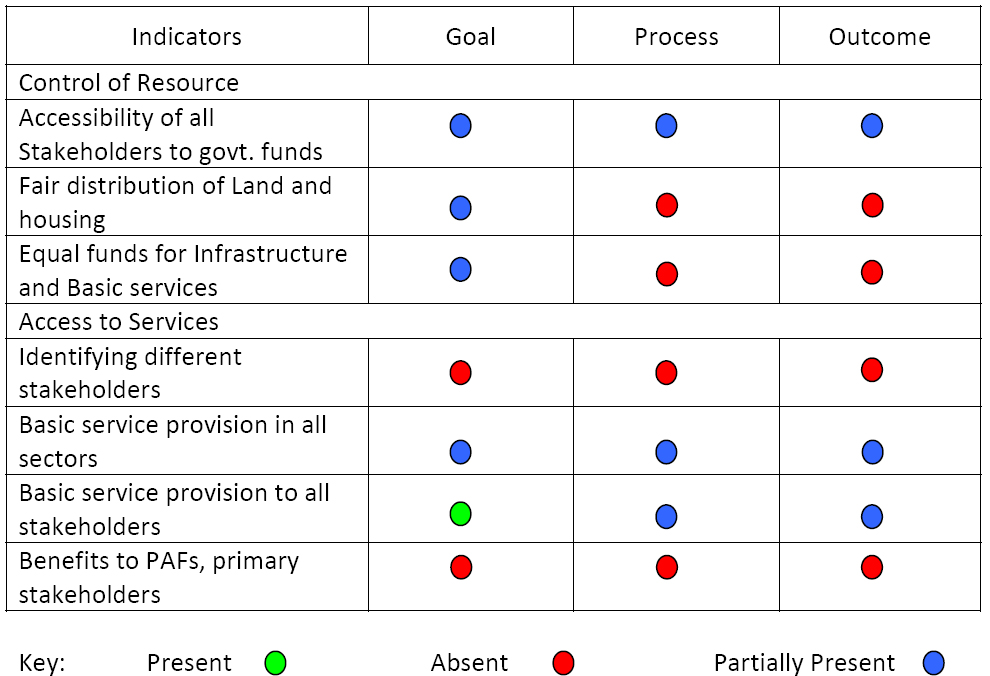

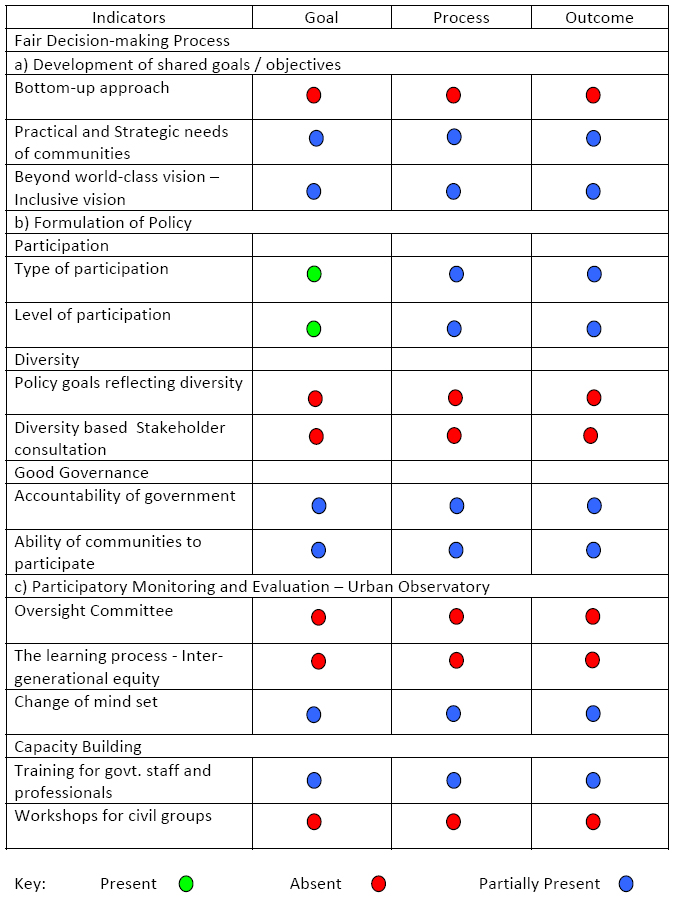

The table below shows the overall framework of social justice principles, criteria and its indicators to analyse NURM. They are categorized into ‘distributional and institutional equity’ context and will be measured in three stages of the policy – goals, process and outcome.

I. Distributional Equity

Distributional Equity involves ensuring that there is fairness in distribution of impacts as well as benefits resulting from the development process (Scott & Oelofse, 1998). The distribution can be broadly seen in terms of material distribution. In case of NURM policy, the material distributions can be measured in two ways, control of resources & access to services.

a) Control of Resources

The most important distribution in NURM is that of financial resources for development. Others include urban resources – land and housing. The indicators are:

- Accessibility of all stakeholders to financial resources. E. g. government funding for civic groups – NGOs, CBOs (for community-led projects); and small private businesses.

- The land and housing should be distributed fairly to all citizens. E. g. not only for business and commercial purposes, but to housing marginalized groups.

- Equal distribution of funding for infrastructure and basic services.

b) Access to Services

Benefits of development like services and the loss incurred by the development both should be distributed equally, ensuring people’s ‘rights to the city’. Indicators are:

- Identification of stakeholders – Account should be taken whether groups are primary, secondary or invisible stakeholders for fair distribution (Scott & Oelofse, 2005).

- Basic service provision in all sectors. E. g. WASH, education, livelihood, health

- Basic services provision to all stakeholders. All parts of the city, specially neglected urban areas. E. g. provision of WASH to slums and low income housing

- Benefits to PAFs – Primary stakeholders like the informal sectors and PAFs affected due to infrastructure development under NURM should be given fair compensation through R & R policy. The burdens should not be only on affected groups. E. g. funds should be allotted to R & R process involved.

II. Institutional Equity

The institutional process in which distribution takes place is essential to understand how social justice can be attained. To measure the institutional / procedural equity, the policy will be seen through the ‘Web of Institutionalization , which is more fully articulated and tested in support of mainstreaming gender planning practices and dimensions of social justice – in policy, planning and management agencies (Safier, 2002, Levy, 1996). The most significant guiding principle for institutional equity is the fair decision-making process at all stages of NURM. Further, capacity building of organisational staff and communities is important in formulation and implementation of NURM policy. The fair decision making process can be viewed broadly in three stages.

a. Development of shared goals / objectives

b. Formulation of policy – participation with diversity – good urban governance

c. Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation of policy – learning process

a) Development of shared goals / objectives

The goals and objectives should be inclusive. Indicators are:

- Beyond world-class vision – visions of common people reflecting their interests and perception of the city, satisfying local needs and not just global demands. All stakeholders should be reflected in goals – bottom-up approach. E. g. all levels of government, civil society, private sectors

- Practical as well as strategic needs of all communities included in the policy goals. E. g. practical needs – provision of WASH, basic infrastructures to marginalized groups. Strategic needs – financial, political and social recognition for empowerment of communities.

b) Formulation of Policy – Participation with Diversity – Good Urban Governance

The formulation of policy involves participation reflecting diversity that leads to good urban governance. Urban population is increasingly becoming diversified due to many reasons like migration from rural areas.

- Type of participation by particular stakeholder. Scope offered in the policy for all stakeholders to enter in the process. Stakeholder consultation with diversity sensitivity. Policy goals / objectives reflecting needs and aspirations of the diverse groups based on– age, gender, class, caste, regional cultures, and minorities and marginalized groups. E.g. focus group meetings with NGOs, CBOs, private sectors in identification, formulation and delivery of projects (community-led projects), and special provisions given to diversity based projects, specific to development of particular group.

- Level of participation – Arnstein’s ladder of participation indicates the level of participation. From bottom to top, the level of participation increases. Citizen control is the highest level that empowers the citizens.

- Accountability of the government to the communities and ability of the communities to participate in the decision making. Distribution of shared knowledge and values through transparent systems to all stakeholders. E. g. municipal office should display the projects details for public information with details of the funds for projects. Politicians should be accessible to the civil groups for decisions.

c) Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation – Urban Observatory

Through learning and better awareness, the future planning can incorporate the elements of social justice bringing transformative changes to planning and policies leading to inter-generational equity. Indicators are,

- Oversight committee formed of civil groups, professional/ research centers and government official as common platform to receive feedback from communities about projects. E. g. makes SIA reports with help of community representatives. Govt. bodies acknowledge the feedback and also give feedback if communities can be involved at any stage for delivering the projects.

- The learning process & inter-generational equity – Recognizes the elements responsible for entrenching inequalities, scope for modifications in the policy for future needs ensuring that future generations do not suffer at the benefits of present generation.

III. Capacity Building

In absence of well qualified staff for formulation as well as delivery of policy, it is difficult to meet desired outcome. Thus, capacity building of different stakeholders can be indicated by:

- Training programs for government staff at all levels and professional staff like planners, architects, engineers.

- Workshops for civil groups like NGO, CBO and communities.

This ‘theoretical framework’ of social justice principles discussed so far provides the basis on which the case of NURM will be discussed.

Measuring the Principles of Social Justice in Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, India

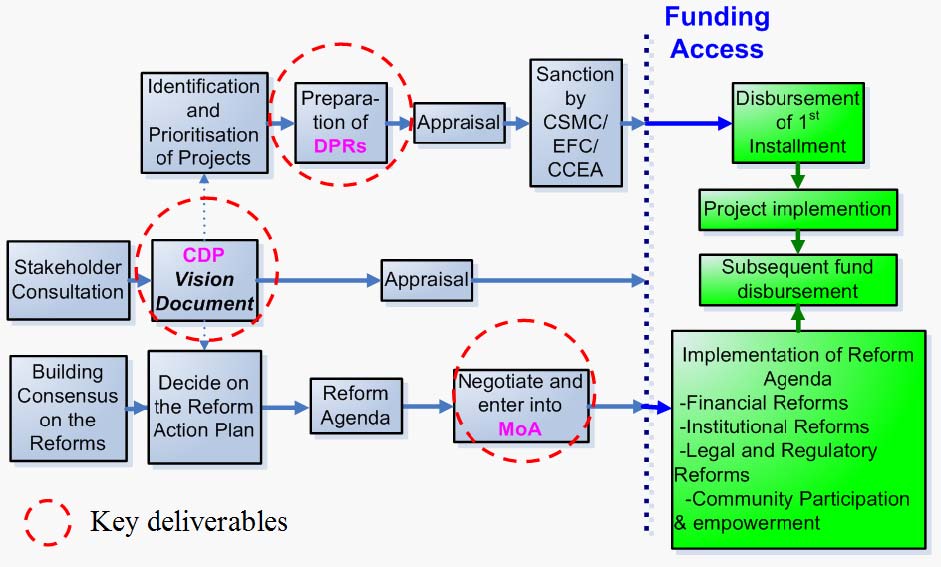

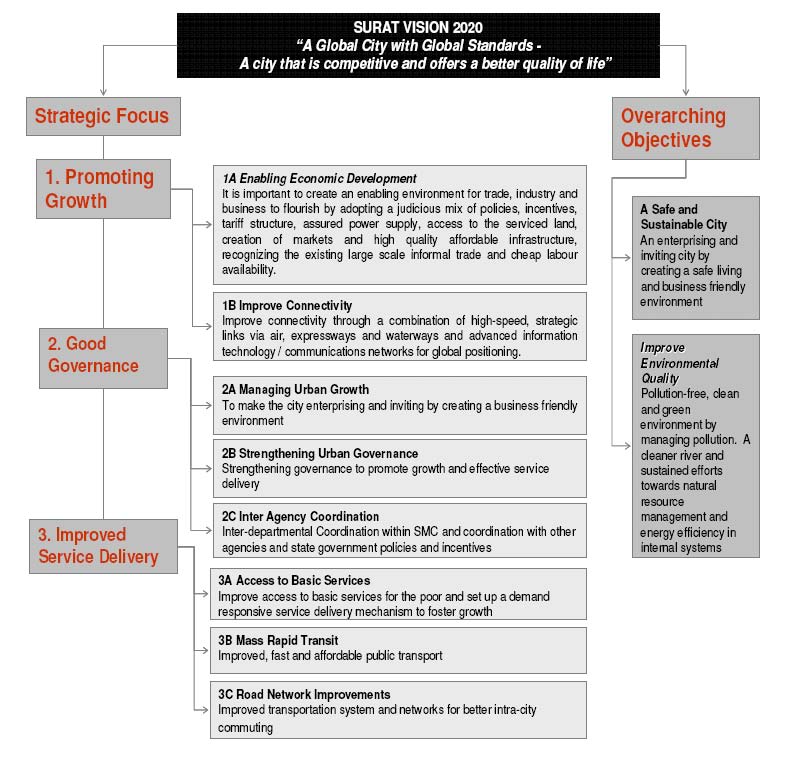

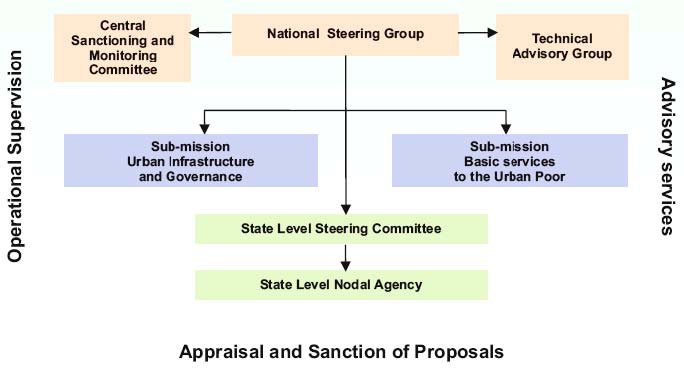

The NURM Mission Statement – “The aim is to encourage reforms and fast track planned development of identified cities. Focus is to be on efficiency in urban infrastructure and service delivery mechanisms, community participation, and accountability of ULBs / Parastatal agencies towards citizens” (JNNURM report, 2005). The Mission has been structured with a clear focus on two important components – urban infrastructure and basic services to the urban poor, with governance reforms as an overarching third component. Moreover, it indicates ‘toolkit’ for formulating CDP for 63 cities across India. The diagrams below show overall process of NURM and Surat Vision 2020 in Surat CDP.

NURM is discussed in terms of policy goals and process and further reference to Surat CDP is made for understanding the details. The analysis is in two sub categories – Distributional and Institutional Equity.

I. Distributional Equity

The Distributional context primarily refers to the outcomes of the NURM policy in terms of control of resources and access to services.

a) Control of Resources

NURM being a funding scheme for urban development, the distribution of government funding pattern and the control mechanisms is most important.

- Accessibility of all stakeholders to government funding

The policy allows only government identified projects to be executed. The ULB decides the projects and ask for funds from the central government along with the approval from state government. The government funds are being highly controlled by the central government. Considering the accessibility of all stakeholders to the fund, there is only one option which is for private developers is to partner with local government through PPP. But the only private groups that could actually get access to funds are the big ones in business, as only they have the capacity and infrastructure to bid for projects and deal with government on PPP basis. The policy does not seem to favor small private sectors or informal sectors to be involved in the process for overall economic growth. There is no mechanism by which fund could be used for community-led projects or community groups like NGOs and CBOs could avail fund for smaller community projects. The civil society at large seems to be alienated from access to government funding for development under the scheme.

- Fair Distribution of Land and Housing

The policy does not directly fund purchase of land, but abides the ULB to follow certain mandatory reforms related to land like the repeal of the Urban Land Ceiling Act and amending the Rent Control Act. These reforms have direct effect on land distribution and housing. The repeal of this Act offers a free hand to the private builder lobby to possess vast tracts of land in the urban area which could result in driving the poor out of the land market. This Act is the only legislative mechanism for enforcing the housing rights of the urban poor that are provided by putting up a ceiling on the possession and ownership of vacant land in urban areas and further acquisition of the excess land for creating housing stock for the urban poor. This could result in a market driven urban development process. PPP implementation models for solving the housing problem of slum dwellers could set a way for selling lucrative public lands to the corporate real estate investors and contractors.“The focus of the policy seems to create infrastructure for a particular class of society, beautification and creating islands of comfort for the rich in urban areas that are slum free in the race to become world-class cities, but with an enormous debt burden” (Jose, 2006, p.5). In this context, the distribution of land and housing is not fair as this ghettoize the poor in the meager patches of land in the fringes or back lanes of the ‘world class city’.

- Fair Distribution of funding for Infrastructure and Basic Services

A comparison of the projects and fund that is sanctioned under the two sub-missions of NURM indicates that there is a greater thrust on Infrastructure projects than the basic services projects to urban poor. Equal thrust seems to be given to development of Infrastructure and provision of basic services to urban poor in the policy mission and goals, but the later project funding seems to be given higher to infrastructure development that could support the global market demands for projecting world-class cities more than supporting the local needs of the urban poor in provision of basic services. The vision does not translate equally in project funding.

b) Access to Services

The following indicators examine fair distribution of services to all stakeholders as well as fair distribution of the impacts or burden of creating those services.

- Identifying different stakeholders

The policy talks in a single voice, to benefit all equally. There is no account of primary, secondary or invisible stakeholders. It also states urban poor as one. Hence, it lacks such account of identification of different groups in a city being affected or benefited differently through the projects.

- Basic service provision for all

The basic service provision is distributed area wise. Services like water supply, storm water drainage provision, sewerage system are distributed in specific areas, mainly outer peripheries where there is no provision as of now. It is a good step towards extending the central city services further to extending urban boundaries. But the basic services distribution do not acknowledge the unrecognized areas within central city like slums. If the mission talks about services to poor, but without identifying who the poor are, the goal does not seem to be meeting in its full intention.

- Basic service provision in all sectors

NURM has selected sectors eligible for funding. It deals mainly with water, sanitation and transportation. Experts from CASUMM, argue that this approach shows there is no “Right to the City” in NURM, as there are no rights based services for citizens, no funding for wage employment schemes, no minimum / equal wages for women like in NREGA, no funding for basic health, education, subsidized social housing or Community toilet services based on needs (CASUMM – URC workshop, 2007, JNNURM – a World Bank Group ‘Program’ with GoI ‘ownership’). The policy focuses strongly only on specific sectors of infrastructure and basic services.

- Benefits to PAFs

The policy does not mention anything about the people being affected due to large infrastructure and transportation projects. City wide projects require clearing large tracks of land from informal settlements. Many times, there are slums and pavement dwellers living along the edges of roads, rail lands, water bodies and any development would first require to move the existing population from such lands. This leads to increase in evictions and displacement of the poor in urban areas. The policy does not talk anything about Resettlement and Rehabilitation of these population. An absence or an improper adoption of R & R process in these projects could further intensify the alienation of poor communities from access to land, infrastructure resources, livelihoods and decision-making process. The burden of development is being bared by urban poor which contradicts the pro-poor goal of the policy.

II. Institutional Equity

NURM is briefly seen through ‘web of institutionalization , developed by Levy (1996), to understand the organisational and institutional processes. It shows the relevant actors constituted at the nodes and their possible power relations through linkages in four spheres; Policy, Organisational, Citizen, and Delivery. The web shows that in policy sphere, it is mainly the central government that plays role. But in organisational sphere, there does not seem to be anyone taking the mainstream responsibility for socially just development. Moreover there are different levels of government within that sphere. In the delivery sphere, again there are different levels of government involved with some consultation of educational institutions. While in citizen sphere, there are no pressure groups or representative political structures involved with the entire process, hence participation being limited in reality.

a) Development of shared goals and objectives

The following indicators examine the formulation of shared goals and objectives that reflect the practical and strategic needs of all.

- The Bottom-up Approach

The policy is highly top-down in formulation of its goals. The goals and objectives have been formed by the Central Government. There are very specific goals and the projects which fit in those goals can only be funded through this policy. One of the goals responds to the urban poor and their basic service needs provision. The lower tier of the government does not have much power to influence the goals formulation, but have to just follow the already laid out objectives. In that respect there is not much scope for the local government, civil society or even private sectors to influence the development of goals and objectives. Hence, there is no shared consensus in the policy approach.

- Practical and Strategic needs of communities

Practical needs of the communities have been quite fairly incorporated in the policy. As one of the main goals is provision of basic services to urban poor, the policy does try to respond institutionally to the practical needs but it does not specify any specific institutional provision for group or community in special need to access these services. As far as strategic needs are concerned, there is no such goal in the policy to empower communities through any financial, political or social recognition. There is no such institutionalization that can lead to mainstreaming the marginalized communities or minority groups through servicing their strategic needs.

- Beyond World-class Vision – The Inclusive Vision

The policy statement very much promises to create world-class cities by fast-track infrastructure development. This definitely reflects the global needs for cities to compete internationally with other global cities. It also suggest CDP toolkit to make city development strategies that can make economic growth to compete internationally. Though, one submission is service delivery, it still lacks the reflection of local needs of communities to be incorporated within this world-class vision. “It is the culmination of a process of neo-liberal urban reforms that has been going on since late 90s. Its predecessors include Urban Reforms Incentive Fund and Model Municipal Law, both of which were formulated on the basis of a set of policy postulates developed by the WB, the ADB, USAID and UNDP” (Batra, 2007, p.6). There is no talk about the development of local civil groups though education, employment opportunities or health facilities. Hence, world-class vision seems to be at the core of the policy with less consideration to local needs.

b) Formulation of Policy – Participation with Diversity – Good Urban Governance

Participation is one of the main over arching goals of this policy. With this initiative, it is to be appreciated for acknowledging this approach in an urban program. But there are still questions of how far the participation has been really practiced in its process and up to what level it has been achieved. There is difference between the stated goals and the actual process. Even though the urban reforms are formed on the basis of decentralization and community participation, it seems that so called community participation is restricted.

There is no mention of diverse groups based on age, gender, caste, class, ethnicity or any minorities or marginalized groups in the policy. The policy addresses citizens as one unified population. This is a diversity blind approach. India is very diverse in its regional and cultural backgrounds, and with fast urbanization and large migration, there is an urgent need to look in to diversity within cities.The following attributes examine the type and level of participation reflecting diversity and good governance through accountability of government and ability of communities to participate.

- Type of Participation

There are stakeholder consultations through common meetings that are carried out for making CDP of cities. The stakeholders surveyed for this consultation are mostly NGO representatives, and private sectors like big land owners, developers, builders, real estate investors. The participation is not directly of the communities. There is no mechanism of direct involvement of community members or their representatives. There is also very little scope for pressure from political constituencies as the entire policy is very much top-down. The local elected bodies are involved with only implementing what is already entrusted on them from the central government. Moreover, there is not much scope for involvement of pressure groups in preparing CDP, since there is already a toolkit assigned for making the vision plan for the city. In this sense, there is no direct link between actual urban poor for whom the services are being provided and the professionals and bureaucrats who are taking decisions for the service provision.

There is no policy goal that responds to a particular group or recognize the diversity at large. It mentions urban poor as one without defining who are those urban poor. There are no specific projects that support marginalized groups or particular group like women to enhance their development. The stakeholder consultation is seems very generic, without mention of focus group meetings or consultation with community groups to understand their particular needs and aspirations.

The Vision of Surat is positioning the city as “Global City with Global Standards” and it claims to be articulated by the citizens of Surat projecting to be a shared vision and supported by the Government of Gujarat. One of the main goals is the year 2021 envisages a “zero slum city” in a phased manner. This shows the CDP talks of very idealist development with global standards. But, the further examination of its process tells a different story, as it does not mention how this is going to be achieved.

- Level of Participation

Referring to Arnstein’s ladder of participation, policy seems to stands between rungs 3 and 4, i.e. Informing and Consultation. There is at some point ‘informing’, since the policy directly informs the citizens which is a one-way flow of information – from officials to citizens – with no channel provided for feedback and no power for negotiation. Under these conditions, particularly when information is provided at a late stage in planning, people have little opportunity to influence the program designed “for their benefit” (Arnstein, 1969, p.45)

However, participation being one of the main goals, there is consultation meetings with selected stakeholders. As Arnstein refers, “when power holders restrict the input of citizens’ ideas solely to this level, participation remains just a window-dressing ritual. People are primarily perceived as statistical abstractions, and participation is measured by how many come to meetings, take brochures home, or answer a questionnaire. What citizens achieve in all this activity is that they have ‘participated in participation’. And what power holders achieve is the evidence that they have gone through the required motions of involving “those people.” This shows that the policy is still far from the top most part of the Arnstein’s ladder where there is ‘Citizen Power’.

There is ‘Community Participation Fund’ for community based projects. This claims to provide opportunities for communities to engage in NUMR (ADB-TA report, 2008). But, there does not seem to be any such initiatives in operation. One reason for this failure to achieve full participation is the delay in release of fund by the central government to carry out participation process (Patel, 2009).

Surat CDP states that the stakeholders involved included NGOs, government organisations (Police Dept., Collectorate, etc.), commercial organisations, MPs, MLAs, municipal councillors, eminent citizens, technocrats and social workers. “From this it would seem that broad based stakeholder consultations have been held in the city and their opinion sought. However, it is not possible to ascertain if there were representatives of the poor in the consultations” (NIUA, 2006, p.9)

One of the city level stakeholder consultation for revised city development plan and for formation of city level TAG was conducted at Hotel Taj Gateway, which is a five star hotel in Surat (UNNATI Report, 2009). It can be seen from the venue of the stakeholders meeting that, it was only the elite class citizens and big private sectors that participated. This clearly does not include the ‘poor’ in the participation. Thus, the criteria of diversity in participation do not seem to be meeting as not any actual community or their representatives that are being consulted to know their needs and aspirations.

- Accountability of Government

Through ‘right to information act’, any information on this policy is available to common people. The fact file of sanctioned projects and their fund allotment is available. But, the state accountability in making CDP shows that, “The development of CDPs by the local governments has begun almost silently, and there is yet to be any public information, awareness or consultation regarding the plans or their preparation process. According to the NURM guidelines these have to be prepared after conducting a wide stakeholder consultation process. The vision of the world class slum free cities is being scripted by the Central government rather than by the people who live in and build these cities and their elected representatives” (Baindur, 2005, p.3). Hence, there is not much of shared knowledge and values between government and communities.

Accountability of the government for provision of basic services like water and sanitation is also diminishing through privatization PPP are at the heart of the reforms envisaged in the NURM. This makes services from being ‘people oriented’ into being ‘consumer oriented’. So far subsidized rates by government supported the poor to survive in cities, but the privatization model can lead to making fundamental rights available only to those who can afford it. Hence, fundamental rights do not remain fundamental any more, but can be bought and sold in the market. “Thus, PPP undermines the concept of welfare state and are a move towards the withdrawal of the state from its obligations towards ensuring equity, equality and well being among its citizens” (Jose, 2006)

For good governance goal, there are some politically correct promises of establishing mechanisms for making city governance more transparent, accountable and enhancing public participation in governance and streamlining administrative procedures for efficient urban management. But the only projects initiated are e-governance for improved performance and service delivery and GIS for utilities.

- Ability of communities to participate

There does seem to be an overall awareness among urban communities about NURM. But, there is still lack of professional skill knowledge which can increase their capacity for a better involvement in the decision-making process. For example, there is hardly any ability of communities to participate in making of CDPs, which is a key step in formation of vision of a city. Further, NGOs and CBOs also seem to lack the capacity in the urban infrastructure and service provision sectors as the urban development concepts are still new in India in comparison to the rural development issues since independence. Hence, there seem to be a need for capacity development of communities and their representatives for better participation and good urban governance.

c) Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation – Urban Observatory

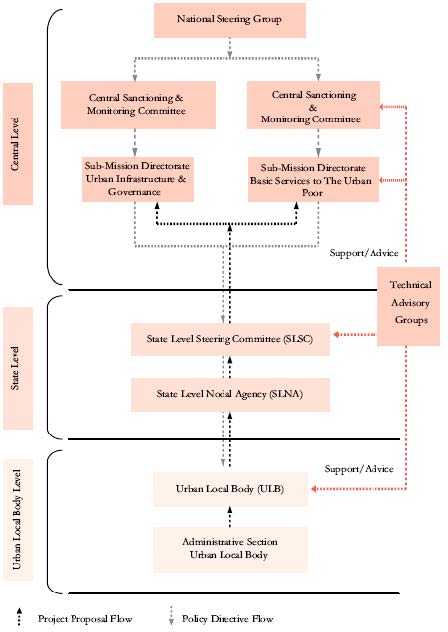

PM & E is an essential part for any policy. The diagram shows the institutional framework for policy monitoring. The National Steering Group (NSG) is the main controlling power which is at the Center for final sanctioning of any proposals and the allotment of funds. Technical Advisory Group (TAG) and Operational Supervision (OS) work through all tiers of the government. This framework shows that it is strongly vertical hierarchy with power relations being top-down. The following indicators further examines PM & E.

- Oversight Committee

The policy does not have any oversight committee that can bring representatives of communities, NGOs, professionals and government officials on a common platform. Though there is TAG which plays an important advisory role to the government, but it does not lobby with any political leaders to support voices from communities. There is no SIA survey or reports made to monitor the process or evaluate the impacts of the policy. The role played by NSG and TAG is mainly related to financial control and monitoring.

Hence, without the common platform between the municipal officials and the communities, neither government receive any feedback from people to their work, nor it gives any feedback if communities could be involved at stage of the formulation or delivery of the projects. This is a very essential link, as through this shared platform, even communities can be directly involved into the system and control and monitor their own provision of services.

- The learning process and the Inter-generational Equity

At present, the main role of learning and theory building seems to be with research & educational centers who are involved with preparation of CDPs and its appraisals and training programs for staff development. For knowledge support, there has been resource centers established like one is at ASCI, Hyderabad to support ULBs and water utilities (ASCI, 2006). The applied research is also carried out by private consultancy firms who conduct the feasibility studies and evaluation of CDPs. However, they are involved with very marginal influence on the entire process of formulation, as their role is more involved with end process of delivery and following the toolkit of NURM.

There is an initiative PEARL (Peer Experience and Reflective Learning) among NURM cities for sharing knowledge and creating networks for cross learning (ADB-TA Report, 2008). But, learning process can also develop through the shared platform between the government officials and the communities. Due to this lack, there does not appear any learning outcome which can feed back to the formation of goals and process of policy. The knowledge from people does not transfer to the policy. Though, there does seem to be certain inter-disciplinary approach to making of CDPs, but at large it still addresses the spatial development of the city. There is a need for a broader multidisciplinary approach for overall development for all. Looking at inter-generational equity aspects, there is certain concern of sustainability for future, but deeper look into the actual realities shows there is not done for inter-generational equity. The infrastructure developments are done keeping the present in view. As discussed earlier, there is no incorporation of R & R into the policy especially when large scale infrastructure projects are being executed under this policy; it certainly misses the concerns for future generations.

There is a basic change of mind set in terms of initiating policies in response to urban development. India had a strong focus to rural development so far, and this policy is a first step in the direction of urban development. This marks the change in mind set of politicians, professionals as well as communities. But, again how far this change of mind set is for creating socially just development is questionable. As the learning process is not a part of the policy, it has not brought much social awareness to issues of equity and just development.

III. Capacity Building

An ambitious national flagship program like NURM being first such scaled-up urban policy in India, it requires greater capacity and management frameworks at all levels and among all actors like government staff, professionals and civil groups.

- Training programs for government and professional staff

The municipal functionaries and project implementing agencies are being trained at research institutes like YASHADA, CEPT and ASCI through workshops for sharing national and global good practices. Also, the Urban Development Ministry is conducting training workshops like Rapid Training Program for elected representatives. The training is mainly oriented to Governance & Reforms, Supervision of Preparation of DPRs and Project Implementation & Management. The CDP formulation and appraisals are being done externally by private consultation firms or relevant universities and research centers. But, there does not seem to be any special training for professional staff like planners, architects, and engineers etc who are involved at the policy formulation. Planning is still seen as spatial planning and not really in terms of interdisciplinary background. The CDP making by the professional is very much physical, lacking developmental approach.

- Workshops for civil groups like NGOs, CBOs

As there is no direct involvement of civil society like NGOs and CBOs, there are not any steps taken to increase their capacity. However, one of the NGOs, SPARC is involved at the TAG for policy monitoring. Since, NGOs are better connected to educational and research centers, their theoretical know how and capacity seems to be fairly good.

Key Findings

The key findings are summarized in to distributional and institutional equity. The indicators are tabulated as being either present, partially present or absent in the policy goals, process and the outcome. The tables below shows that some of the indicators are present in the goals, but later does not exist in the process or the outcomes. As a result, distributional and institutional equity looks to be partially achieved in the case.

The distributional equity table shows that overall control of resources is partially present in the goals but disappears later in the process and outcome. Not all stakeholders are able to access the fund. The land and housing though initially shows to be for urban poor, but at the end, it is favoring the market. There is unequal focus on infrastructure and basic service provision. There is no identification of different stakeholders though policy promises basic service provision to all. The goal talks about urban poor, but without proper R & R mechanism vital to large scale development process, the urban poor seems to bare the burden of development. Overall, distributional equity is partially achieved.

The institutional equity table shows that in the process of decision-making, the policy goals are top-down. There is no shared consensus at goal formulation. The goals address practical needs of urban poor and at the same time promises to set global standards for the city. Participation is one important goal, but the process is not as desirable when the type and level of participation that should reflect diversity is analysed. Hence, it does not translate into outcome. For PM & E, there is policy’s own institutional framework for monitoring the projects and funds, but it is not based on involvement of communities in to the institutional process. As this is the first scale-up urban policy in India, there are certain efforts for capacity building of municipal staff. But there still is a need for training at higher level staff in policy making.

Some possible future directions for NURM and overall planning practice in India could be looked at through the analysis of the above key findings.

- Policy Approach

NURM is a highly top-down process with center holding much of the powers, in terms of approval of projects and release of funds. Though a top-down process is important to deal with large scale planning and complexity, there should still be scope for bottom up process as well as horizontal collaborations between different stakeholders. There is a need for more decentralized system, where local authorities can take more decisions, being closer to the communities. This helps in creating room for manoeuvre for local authorities which can mainstream their responsibilities to bring transformatory principles for socially just development. The horizontal relationships across different actors provide opportunity for civil society’s involvement in to the process. At present, all projects identification is with the local government. However, there could be some scope for community-led projects, where communities could identify the projects and get them funded by the government.

- Sectoral Distribution of Funds

NURM rightly addresses the acute need of infrastructure and basic services needs of the cities in India. The mission aim though seems to be politically correct, but it seems to be neglecting many other essential sectors that need attention for holistic development. There is no mention of education, health and livelihood. The guidelines provided for CDS do not include the employment sector. When central government releases huge fund, there is a need to look at all sectors equally. Moreover, there is more stress on infrastructure development which is in response to global needs and fewer funds allotted to basic services which are local needs.

- Participation and Good Governance

Participation and good governance being part of the main goals of the policy is a good step towards a socially just process of development. But, certain institutional mechanisms do not seem to translate these concepts well from goals to outcome. The policy is diversity blind and does not define urban poor. For effective participation, there is need to consider diverse population and consider their involvement at various level in the policy. The transparent system of shared knowledge and values could improve accountability of the government and help achieve good governance.

- Policy Monitoring & Evaluation Framework

The present policy monitoring is central, which could be decentralized to monitor the process at the local levels based on participatory approach. There could be a common platform between government, community representatives, NGOs, professionals, academicians and private sectors. Some form of oversight committee could be an option, to bring quality monitoring and evaluation of the process. This could further build up a learning process leading to inter-generational equity.

- Capacity Building

As this is a first central urban policy, there are serious challenges for capacity building of municipal as well as professional staff. For a successful outcome, efforts are required towards training qualified staff to handle large-scale urban projects. Multi-disciplinary approach and feedback learning process could also lead to capacity building of experts and professionals.

Conclusion

A policy like NURM is definitely a stepping stone towards urban development in India. A beginning of such a national program focused on pro-poor goals with participatory approach and governance reforms is a first such approach ever taken in the history of India. It is a comprehensive strategy which very much addresses the current needs of urbanization. For a large country like India with billion plus population, the challenges of urbanization are complex and diverse and can not be solved exclusively by city and state governments. There is a need for a top down approach from Central government to guide the process of urbanization across different cities, especially with limited resources. On an optimistic view, the progress should not be unnoticed and has to be appreciated.

However, considering the findings of the analysis, there seems to be a need to look at critically the institutional mechanisms and the resultant distribution pattern. Overall, while NURM intends to bring urban reforms and renewal and make world-class cities in India, it lacks certain dimension of social justice in doing so. The pro-poor goals of the policy are not being articulated fully through its institutional mechanisms which are more market oriented and hence the outcomes are not fairly distributed within and across cities of India.The detail examination of policy suggest further scope of improvement and future direction for urban development in Indian cities. There is a need to start thinking in a broad collaborative manner for formulation and implementation of policies. Building vertical relations both ways, top down and bottom up as well as building horizontal relations across different actors create synergy in the planning process. Consideration of diversity and innovative ways of engaging communities in to the process provide scope for reflecting practical and strategic needs of people who live in the cities. Further a good participatory monitoring and evaluation of the policy provide learning and feedback platform for addressing current needs as well as making development sustainable for future generation.

Thus, in the era of globalization and neo-liberal agendas forced on the cities, the dualism that cities need to respond between global demands and local needs, the role of urban policies is very crucial. Urban programs like NURM are very essential to analyse to understand how it can create socially just cities for present as well as future generations. In the run for creating world-class cities, the vision for cities is increasingly becoming exclusive, selecting the rich and neglecting the poor. The social justice in terms of distributional pattern and institutional process, both is becoming increasingly unjust. This calls for an immediate need for urban policies to be based on inclusive vision for ‘socially just cities’ rather than ‘world-class cities’.